The Transformational Power of the Right Spice

Marcus Nilsson for The New York Times

Reims, Blend No. 39, named for the French city famous for its gingerbread and featuring cinnamon, mace, ginger and star anise.

By ALEX HALBERSTADT

Published: April 4, 2013

There’s an eschatological thrill to walking into La Boîte, a shop wedged between an auto-repair garage and a dismal fenced-in garden on the far west side of Midtown Manhattan. At a cultural moment that has given us a storefront dedicated to artisanal mayonnaise, La Boîte manages to advance the genre. The shop is open to the public a total of 12 hours a week. Inside, it’s serene and nearly empty. At the entrance, a plexiglass obelisk contains a tin the size of a paperback packed with minuscule spiced biscuits (pronounced bis-KWEE; they’re cookies, and the tin costs $65). Farther in, there’s a display with numbered canisters that look as if they encase costly Japanese cosmetics but in fact contain spice blends that have been doled out with a jeweler’s parsimony. As I took in the glossy photos of pods and rhizomes lining the walls and handled the decadently cool, silvery pucks, I couldn’t help wondering whether this is what ancient Rome must have been like near the end, before the Vandals trashed Palatine Hill.

Yet there is intelligence behind La Boîte, and it belongs to Lior Lev Sercarz, a man who describes himself as a “spice therapist” and considers spices to be both a vocation and a mission. Vocationally speaking, he has been devastatingly effective. He’s a purveyor to some of the best chefs in New York and beyond. Le Bernardin’s Eric Ripert has all but forsworn spices from other sources. Lev Sercarz was one of the first people Marc Forgione called when he opened his eatery on Reade Street. Blends from La Boîte turn up in pain d’épices in Paris, in hipsterish fried chicken in Philadelphia and in pasta with clams in Singapore. Generally, restaurant people make up a hard-bitten demographic, so when I repeatedly heard words like “magician” and “visionary,” I imagined I might meet a nutmeg-dusted Timothy Leary.

As a home cook of middling talent and curiosity, I hadn’t given spices much thought, contenting myself with the doleful little McCormick jars in my pantry, some of which were probably getting old enough to drive. In this, I’m apparently not that different from some professional chefs. “Most young chefs don’t know much about spices,” Forgione says, “and they tend to stick to what they know.” Lev Sercarz adds that culinary students “aren’t taught how to taste and smell.” One bright March afternoon at La Boîte, amid several dozen bulk containers of raw spices, Lev Sercarz told me to forget everything I thought I knew, and he set out to re-educate me in the mysterious byways of flavor.

The spices he laid out smelled and tasted nothing like the time-forgotten powders in my pantry. They were steroidally potent, burrowing in my nostrils like tiny aromatic voles. After giving an umber mound of cumin a whiff, I felt as if someone had probed my sinuses with a wire brush. I realized then how ignorant I had been.

Take pepper. Even the simple black peppercorn tasted smokier and more complex than I remembered. Lev Sercarz’s come from Tellicherry, on India’s Malabar Coast, just north of where Vasco da Gama debarked in 1498, braving scurvy to procure spices for the Portuguese crown. Green peppercorns, an unripe version of the black, were vegetal by comparison. Pink peppercorns aren’t peppers at all, but dried Brazilian berries that tasted mild and sweet. There was tail pepper from Java, which tasted of pine resin and citrus, and wild Tasmanian pepper that crinkled on the tongue sweetly and then numbed it disconcertingly, like a curare-tipped dart. Sarawak pepper from Borneo, frankly, is too peculiar to describe. White pepper is actually black pepper put through a process called retting: the peppercorn soaks until the skin decomposes, then the seed is dried. Paul Liebrandt, the chef at Corton, calls it “hospital pepper,” because much of what we consume has been retted poorly and begins to ferment, giving it a medicinal stink. The white pepper at La Boîte smelled heavenly, with a texture somewhere between good chocolate and truffle, followed by a flavor both mild and strange. This, Lev Sercarz made clear, was but a cursory glance at the syllabus to Pepper 101.

When I wondered out loud about how much spices could really matter — weren’t they a mere flourish after the difficult work of cooking was completed? — Lev Sercarz invited me for a demonstration in his home kitchen. There, he seared filet mignon coated with Pierre Poivre (La Boîte Blend No. 7, with eight varieties of pepper); imagine an IMAX version of steak au poivre, the meat tasting the way neon looks. Then he did the same with Kibbeh (Blend No. 15, mostly cumin, garlic and parsley), and I could have sworn I was eating lamb: the mild tenderloin had turned gamy. That’s cumin, Lev Sercarz explained, which the palate tends to associate with lamb. Next he cooked a cube of salmon in olive oil infused with Ararat (Blend No. 35, with smoked paprika, Urfa chilies and fenugreek leaves), transforming it into something I would have guessed, with eyes closed, to be pork belly. That, he said, was the smoke. Spices, I was learning, not only behave as intensifiers and complicators but also, in the right hands, can redraw the boundaries of flavor and confound the brain. For the finale, Lev Sercarz dropped a pinch of Mishmish (Blend No. 33, with crystallized honey, lemon zest and saffron) into the bottom of a glass and covered it with an inch of lager. The bitterness and hoppy flavors were gone — the beer smelled and tasted like a gingerbread milkshake. (I reproduced the trick for Garrett Oliver, the brewmaster at the Brooklyn Brewery, and he, too, was struck, staring into the glass as if he had glimpsed his future at the bottom.) With that, Lev Sercarz rested his hands on his hips and cocked his head, with a voilà expression, indicating the demonstration was over. Then he grinned.

The world used to smell a lot worse, according to the Yale historian Paul Freedman, author of “Out of the East: Spices and the Medieval Imagination.” Our ancestors knew terrible odors and, perhaps as recompense, lavished fortunes on the exalted ones. The most valued were the sweet, exotic aromas of dried spices, which traveled thousands of miles from inscrutable Asian lands and commanded often staggering prices — in Roman times, a pound of cinnamon oil cost a centurion’s salary six times over. Since antiquity, the nobles of Europe fumigated their homes with spices, encrusted their food with cardamom and pepper and handed out medicinal spice blends mixed with sugar to their guests as end-of-meal treats. Spices were believed to denote goodness: if the smell of hell was imagined to be excrement, Freedman suggested, heaven was believed to smell like camphor and mace. Denizens of the medieval world carried sweet-smelling spices in perforated containers called pomanders, believing they warded off the miasma that spread diseases like malaria and plague. And until the 17th century, when the chef François Pierre de la Varenne and his fellow Frenchmen established a vogue for mild herbs and natural flavors, the highfalutin food of Europe was ostentatiously overseasoned.

If the story of spices is that of expanding global horizons, than Lev Sercarz is a suitable modern-day avatar. He grew up on a kibbutz in Galilee, near Israel’s borders with Lebanon and Syria, and comes from sturdy German-Belgian-Transylvanian-

After cooking at a popular restaurant in Lyon, Lev Sercarz found himself working as a sous chef at Daniel in New York. He worked there for four years, eventually running the kitchen of the chef’s catering company, but soon enough the spices beckoned. “I knew I had to leave when the chime of the orders coming into the kitchen began to irritate me,” he told me. He took a day job heading up Citigroup’s executive dining room and worked on blends after he left the kitchen in the early afternoon. In his basement apartment, Lev Sercarz sorted raw materials, weighed, toasted, ground, mixed and then packaged the spice blends. He spent the bulk of his time sourcing the most flavorful ingredients, a dodgy prospect, as most importers sold vast lots to institutional buyers and were nonplused by Lev Sercarz’s probing about quality. His fastidiousness and late nights of experimentation began to draw high-profile clients, and word about his blends began to spread.

Lev Sercarz drew up a business plan and tried to raise a six-figure sum to start a shop that would combine his interests in spices and baking. He would package the blends and sell the biscuits to show them off. He failed to raise a single dollar. One night, on the phone, Roellinger asked what he actually needed to start the business. Lev Sercarz replied, a room, an oven, a $15 coffee grinder and some containers. “See,” the Frenchman said, “you don’t actually need the money. Just go ahead and start.” The shop opened in 2010, offering a collection of 41 blends that took Lev Sercarz six years to develop. Each relied on a triad of principal spices augmented by a supporting cast — the number of ingredients ranges from 9 to 23, and Lev Sercarz does not divulge them.

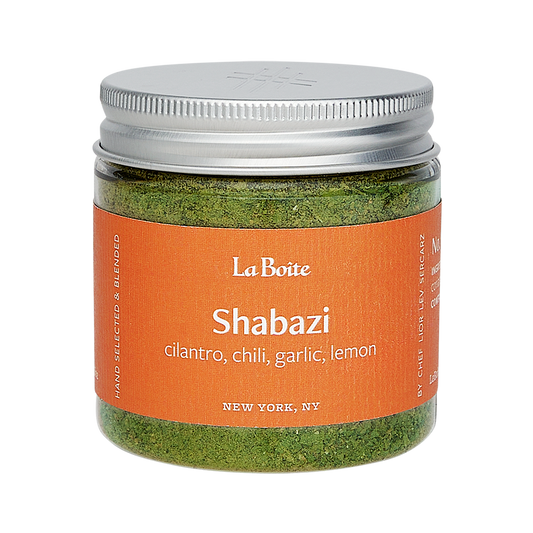

But he delights in their propagation. He told me about a recent outing to Federal Donuts in Philadelphia, where he overheard a young guy say to a friend, “You got to try the Shabazi chicken, it’s out of this world.” The fried chicken was cooked with and named after one of his blends, which Lev Sercarz named after a 17th-century Yemeni-Jewish poet. The fact that these locals — his description made them sound like the most lumpen of bros — relished his work made Lev Sercarz feel at home in the world. “It was probably my proudest moment,” he told me.

Still skeptical of the missionary aspect of Lev Sercarz’s business, I asked about his so-called spice therapy, and he agreed to show me. I told him a little about my past, and at a late-night session at La Boîte, he made me a blend. I grew up on the periphery of Moscow during the waning years of the Soviet Union, and Lev Sercarz chose ingredients that spoke to him of Eastern Europe but also, he said, of New York: poppy seeds, coriander, sesame, paprika, caraway. He named it Stavia, a play on the Latin name for the black nigella seeds that dotted the rust-colored mixture. He instructed me to put it onto nearly everything.

At first, I had to admit to disappointment. Compared with more exotic blends inspired by Turkey and Indonesia, Stavia tasted — if you can say this about a taste — homely. Still, I dutifully plastered it on seared tuna, threw it on salads and rained it on pasta. I even flung Stavia onto frozen pierogies and store-bought chicken salad. The spices made everything taste more compelling, and there was an appealing stab of heat from the paprika, but the flavor transformation I expected never came.

Then, on Day 3, I noticed that the Stavia was affecting my mind. As I ate, my brain began to regurgitate childhood memories. First there was my mother’s beef flank, simmered in gravy to a punishing doneness; then the smell of a sweet clear brew, dispensed from Moscow store counters, called birch juice; and finally I recalled mushrooms. My great-grandmother and I foraged for them around the polluted lake in the village where she rented a cabin in the summers, and afterward we combed the woods that ran along the wheat fields of the collective farm. She showed me how to pickle and jar them, and in the fall I presented the results to my parents and assembled kin, who congratulated me and bit into the mushrooms with an exaggerated relish, at least until the food poisoning set in. I must have been about 6. I remembered this in front of a plate of Stavia-dosed potatoes, where I sat engrossed until someone at the table waved a hand in front of my face.

Lev Sercarz had mentioned that when he designed blends for clients, he learned as much as he could about their backgrounds and how they lived. “Sometimes I feel like an investigator,” he said. The things we eat as children haunt us as adults “whether we like it or not,” he added. “Some people embrace where they come from, some rebel, but in the end, it really doesn’t matter.” When I spoke to Srini Pillay, a psychiatrist at Harvard Medical School who studies the neurological effects of spices, he told me that olfaction is the only sense that communicates directly with the cortex in the brain without pausing at the relay station of the thalamus. “Smell has a very potent effect on the brain and, as a sense, it’s very primitive,” he said. For all its modish decadence, Lev Sercarz’s trade is older than the Silk Road; the spices in the two-ounce jar he gave me provided a neurological link to my patrimony, however fleeting.

At the premiere of Lev Sercarz’s spring/summer 2013 collection, titled “The Tip of the Sword,” friends milled around the shop while an employee handed out the postage-stamp-size biscuits. I nibbled on a square seasoned with Urfa chilies and dark chocolate. Lev Sercarz grasped hands and patted shoulders, his periwinkle lab coat smudged with a web of ocher and brown powders. He asked how Stavia had worked out, and I told him that I wasn’t absolutely sure I liked the taste but that it had made me remember odd, embarrassing things about my childhood. He looked at me as if he’d been expecting my answer.

“You couldn’t have paid me a bigger compliment,” he said.

A version of this article appeared in print on April 7, 2013, on page MM64 of the Sunday Magazine with the headline: The Spice Is Right.