La Boîte's Lior Lev Sercarz Is a Spice Wizard (and You Can Be One, Too)

Written by Carey Polis

Photography by Clay Williams

Duct tape. That’s the key to starting up a business. Sure, money is great, plenty of space is nice, and you gotta have talent. But when you just need to get off the ground, you need duct tape.

At least, that’s how it worked for Lior Lev Sercarz, the founder of La Boîte, which creates intricate custom spice blends for some of the best restaurants and bars in the country, as well as for home cooks.

Back in 2006, when Sercarz first started out, he had only a small freezer—nowhere near big enough to store all the dough he needed to create his seasonal collection of French biscuits, made with the spice blends he’d been tinkering with. And yet, as overstuffed as it was, that freezer was all he had. And he had to get the door to close somehow. His solution: duct tape. It kept the door closed until he sold his first blend, Isphahan, which features limon omani (dried lime) and cardamom, to chef Laurent Tourondel for the now-defunct restaurant BLT Market. In fact, it kept the door closed for three years, during which time he developed about 30 new blends (with ingredients like fenugreek, annatto, and verbena), wooed new clients (La Boîte is now the exclusive provider of spices to Le Bernardin), and sold more blends (they’re everywhere from Publican Quality Meats in Chicago to PDT cocktail bar in New York City), until finally he was able to sign the lease on his current minimalist Manhattan retail store and workshop.

Today, Sercarz doesn’t need duct tape for his (much larger) freezer. Actually, he has almost too much retail space, at least by Manhattan standards—customers have ample space to walk around and look at La Boîte’s 59 blends, all of which contain between 9 and 23 ingredients. The man knows from spices.

It was this mastery of a trade both arcane and everyday that made Sercarz the ideal candidate with which to begin this fall’s Out of the Kitchen series. Throughout the next few months, Bon Appétit will be apprenticing with eight culinary artisans across America, from knife forgers in Georgia to soy wizards in California, then applying those new skills in our home kitchens (and workshops). For each of the eight, you can expect two stories: the first focusing on how the artisans rock their little niche of the food world, the second showing our attempts to translate their professional expertise to our own lives—i.e., the lives of regular home cooks.

I.e., me. I’m a perfectly capable cook, comfortable deploying spices on just about anything I eat. (Za’atar on my yogurt? Check!) And I’d had Sercarz’s spices before—his Marrakesh No. 6 blend winds up improving a lot of the fish and vegetables I make—so I was super excited to get a deeper understanding of his methods and thought process. What Sercarz is doing is not as simple as choosing a few flavors he likes, stirring them in a bowl, and then throwing them in a jar. Rather, he’s all about meticulous sourcing and mindful blending. To get the roughly 120 ingredients he uses regularly, like muntok (an Indonesian white pepper) and dhania (similar to coriander, but more citrusy), he relies on 15 select suppliers, who provide him with mostly whole ingredients—not pre-ground spices—that are of much higher quality than what you’d find at the grocery store.

The blends themselves aren’t determined by the food they’re going to accompany—they’re inspired by something or someone in Sercarz’s life. For example, Apollonia No. 29, is named after his friend Apollonia Poilâne, the chief executive of the famed Parisian bakery Poilâne, and contains cocoa and orange blossom—not typically considered “spices,” but for Sercarz a spice is any dry ingredient that is edible and can be blended. That includes herbs, barks, sugar, salt, and so on. It may not be the dictionary definition, but it allows for creativity. MishMish No. 33 contains crystallized honey; Orchidea No. 34 features orchid root.

And while Sercarz recommends certain spices for certain food categories (Isphahan works nicely with chicken, legumes, mollusks, and soup), he purposely imposes no culinary restrictions on his blends.

“If you are a seafood restaurant and you need to make a blend for fish, I will make it, but I will make it in a way that you can use it for other things,” he says, declaring, “I refuse to make a blend just for fish.”

The blending process is where Sercarz’s skills are immediately evident. Immediately after I ask him to demonstrate his process, he begins grabbing jars of spices from his work table. First into a small glass bowl go three green cardamom pods, then more: black pepper, aniseed, clove, rosebuds, caraway, cayenne, allspice—each into its own little bowl. Then he weighs each ingredient (in grams) with a digital scale—a “must” for any home cook, he says. (The BA test kitchen recommends the Escali Primo.) After many years of creating blends, Sercarz has a fairly exact sense of how much of each ingredient should be added.

It wasn’t always that way. Although he’d worked for 20 years as a chef—including five years at Daniel—and had developed a reputation as a guy who knew spices, he still had a lot to learn when he opened La Boîte.

“When I started, I don’t think I’d ever eaten a whole pod of cardamom,” he admits. But now he is way beyond those days. In fact, he snacks on spices as his breakfast and lunch.

“God knows how many tablespoons of black pepper I eat in a day,” he says. Apparently, the black pepper diet works well; Sercarz, who is in his early forties and trim, with an artist’s mop of silver hair, doesn’t go to the gym or do any sort of exercise.

Anyway, once Sercarz has all the ingredients in front of him, he thinks about which to toast. Toasting releases essential oils; think of it like the spices are sleeping, and toasting wakes them up. In this case, he doesn’t toast the cayenne (which is already ground) or the rose because both will burn.

Then he grinds. He decides to leave the aniseeds whole to give some texture to the blend, and because he just likes how they taste as is. He never (never!) uses a mortar and pestle. “Leave it as a decoration for your living room or kitchen counter,” he says. The strength you need to operate a mortar and pestle is likely to send seeds flying all over your kitchen.

But with a spice grinder, he says, “you can be 3 years old or 80, the result is exactly the same and very fast. You can obtain exactly what you need.” (He recommends Krups.)

After he grinds the spices, mixes all the ingredients together, and places the blend in a jar, Sercarz usually walks away. He checks email, he has a cup of coffee. Perhaps in an hour, he returns to taste and see how the spice lingers on the palate. He rubs some into his fingers to feel the texture and to see if there are any big, un-ground pieces, and if he’s happy with the consistency. He looks at the color. And when he opens the jar, he smells the lid and not the jar itself. Sercarz is after the essence of the spice, like smelling the perfume tester but not the bottle. From there, he tweaks proportions and ingredients as needed.

“I don’t make a blend for the sake of making a blend,” says Sercarz. “Nowadays it is about collaborations on projects.” That means anything from making a Milk Chocolate Bombay ice cream flavor with Jeni’s Ice Creams to creating spices for kale chips to working with Philadelphia-based chef Michael Solomonov on his growing empire of restaurants.

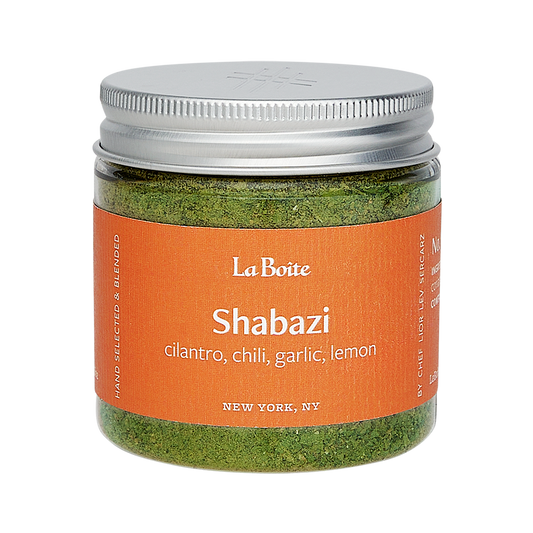

The Solomonov collaboration, in fact, has been one of Sercarz’s most satisfying. Once, he was sitting in Solomonov’s Federal Donuts—whose fried chicken featured Shabazi No. 38, a blend with green chiles, parsley, and coriander—when he happened to overhear a customer say, “Oh man, the chicken shabazi is out of this world.” For Sercarz, that was the ultimate praise.

“I guess I can retire,” he joked.

Retirement doesn’t seem to be in the near future, however. For now, Sercarz has a lot he wants to accomplish, like working more closely with farmers to improve the quality of their spices. In New Orleans, for example, the city’s culinary identity is tightly bound up with cayenne pepper—yet most of the cayenne consumed in New Orleans actually comes from China. To reconnect the city and its iconic spice, Sercarz is working with Louisiana farmers to grow chiles on their own turf.

Moreover, he’s on a mission to teach American cooks that spices are their friends—even their sous chefs. And while he acknowledges that the smart, deliberate, and liberal use of spices is not yet quite part of our culture, he remains optimistic that the artisanal revolution that has taken place around, say, coffee and charcuterie will one day encompass spices like dhania and muntok.

“We’re getting somewhere,” he says, “but we’re far.”

Spice Up Your Life in 6 Easy Steps

1. Sketch out the blend on paper, to get a sense of what ingredients you want to work with, and how many grams of each to add.

2. Place each spice in a small glass bowl and weigh it. Record the amounts!

3. Decide what you want to toast—avoid toasting anything that’s already ground, because it may burn. To really get a great toast, place spices on an even layer on a baking tray and put in an oven set to its lowest temperature for about an hour. If you don’t have that kind of time, toast the spices in a pan over low heat for a few minutes. Once you can smell the spices, they’re ready.

4. Grind the toasted spices together in a spice grinder. Think about whether you want a coarse or fine powder—that will affect how many seconds you grind for. If you plan to use your mixture as a rub, go coarser. If the blend is more about subtle flavor, go for a smoother texture.

5. Mix all spices together in a bowl. Place in a jar and close the lid. Walk away.

6. Return in an hour. Smell the blend. Try it with some food. Rejoice in your creation! Or… go back to the drawing board!