F&W’s Masters Series: Lessons from Spice Whiz Lior Lev Sercarz

By Emily Thelin

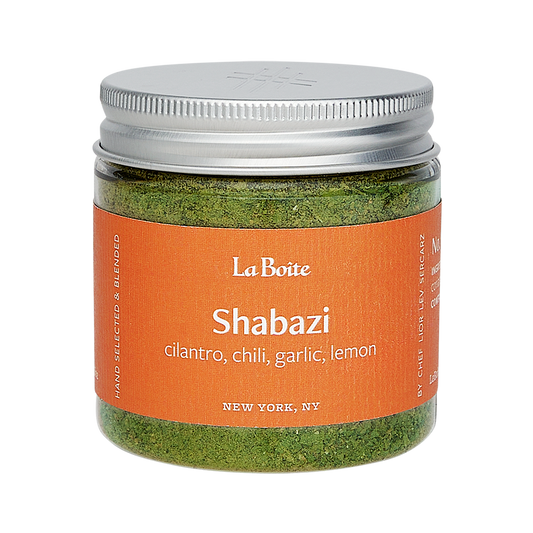

“Pierre Poivre is a big idol, and one of my spice blends is named after him,” says spice master Lior Lev Sercarz of New York’s La Boîte à Epice. “He was predestined to work in spices—his name translates to ‘Peter Pepper.’” Here, Sercarz offers an ultimate guide to spices, from how they grow to how to pair them with chocolate.

Spice expert Lior Lev Sercarz.

Photo © Thomas Schauer.

When star chefs like Eric Ripert and bartenders like Jim Meehan need a custom spice blend, they turn to Lior Lev Sercarz. Born in Israel, Sercarz trained as a chef in France and cooked for nearly 20 years before starting his New York–based spice business La Boîte à Epice in 2006. With regular trips around the globe to source close to 120 raw materials, he sells 41 blends of his own plus another 20-odd custom creations for restaurants around the world. With evocative names like Breeze and Iris, his blends innovate, like Breeze’s combination of tea, anise and lemon. Ask him what spices go with, say, chicken, and in less than a minute he can offer up a dozen creative ideas, each more delicious than the last. Now at work on a cookbook, he will also release a line of spiced chocolate bars this fall. Here, Sercarz explains what distinguishes beautiful spices from ordinary ones, and what spices go best with chicken, salmon and green leafy vegetables.

How did you first fall in love with spices?

The food of Israel is very complex and uses many different spices. Growing up in Israel, whether you like it or not, you are exposed to it. I started cooking because my mom was working and would ask me to jump in when she worked late. I found I really liked it. I began cooking professionally, and later moved to the Paul Bocuse Institute in Lyon. I saw a lack of understanding about spices that really surprised me—how little we use, and if we do use it, not necessarily in the best way. Throughout my 19-year cooking career, again and again I realized that people spend a lot of time sourcing great meat and fish and vegetables, but when it came to salt, pepper and other spices, they used whatever was available. Nobody ever stopped to say maybe there’s something better or more suitable for our needs.

I did an externship at Les Maisons de Bricourt with [three-star] Brittany chef Olivier Roellinger. He’s known all over the world for his use of spices, and he’s a very kind person. When he saw the interest that I had, he encouraged me to research the cultural aspects, the history, and religious aspects, even the financial aspects of the spice trade throughout history—from sourcing and growing the spices through trading them, to the plate in the kitchen. That just reinforced my passion; I just found it fascinating. There’s no real school for the spice trade, since it’s so complex. You have to learn on your own.

Who did you look to for spice history?

Olivier Roellinger is definitely my main mentor in spices as in life. But I found models throughout spice history: definitely the explorers of the 12th, 13th and 14th centuries. Pierre Poivre is a big idol, and one of my spice blends is named after him. He was born in Lyon, where I went to culinary school. He was predestined to work in spices—his name translates to “Peter Pepper.” He was sent by the French East India Company to do a few things: First of all to spread the word of God, since Christianity played a major role. And he was appointed Governor of the island of Mauritius.

Later, he got caught in a naval battle in Southeast Asia, and they had to amputate part of his arm after he was hit by a cannonball. But he was an enthusiastic botanist. The Dutch and Portuguese colonies had a monopoly over the spice trade in those days. So he organized these underground trips to smuggle spices, planting clove and nutmeg and pepper on Mauritius and later Madagascar. So the fact that we can all afford those spices today is in many ways thanks to him.

What distinguishes a beautiful spice from an ordinary one?

In order to judge the quality of the spice, visually you can tell when something looks dusty. It’s easier when you buy whole spices to judge their color and shape: Are they whole or broken into little pieces? When it says “whole pepper” and half is powdered, something’s wrong. Or if it says “nutmeg” and there’s more powder or chips in it, it means they’re old and fell apart into powder because there’s no more humidity left. But ultimately there’s no alternative to tasting. The real key is to do comparative tastings, getting the same ingredient from different sources, and seeing which is best. And as with so many foods, it’s important to know your source. The same way you trust your local greenmarket guy or fishmonger, it’s good if you can find a source of good spices that you can rely on.

How do different spices grow?

Most of us think that spices come from a factory in the Midwest, when they grow all over the world. A lot of spices are still grown and harvested by hand, not to avoid machinery, but because of the landscape. Spices are like other agricultural products: They need a certain climate or geography. They tend to grow on very steep hills, on family-owned parcels that are typically very small. Spice farms aren’t like corporate operations in the Midwest that grow thousands of acres of wheat or corn. If you’re a spice farmer, maybe you have a couple of rows of pepper, some vanilla flowers, maybe a tree or two of nutmeg. You bring your yearly production to a broker who buys from all the farms in the area. From that moment on the journey pretty much starts.

Nutmeg grows on a tree.

Peppercorns are the berries of a pepper bush. Black, white and green peppercorns all come from the same bush, they’re just at different stages of maturity. White pepper is black pepper whose skin has been removed.

Pink peppercorns are not technically peppercorns. They’re a berry of a Brazilian bush that is used more in flower arrangements than in cooking.

Cloves are the dried fruit of a clove tree; they grow in little clusters. It’s a very beautiful tree with beautiful flowers.

Cinnamon is the bark of different types of trees, depending on the cinnamon variety. It’s harvested by scraping off the bark.

Vanilla is the fruit of the vanilla plant. Vanilla requires a lot of labor, because each pod has to be pricked with a needle to allow the beans to mature. In nature, the birds prick the beans and start the ripening; today it’s done by hand.

What is the typical journey of a spice from farm to kitchen cupboard?

So spices are grown, then harvested and dried. Most are still air-dried, then sorted out by quality, size, etc. Then they start the journey, going from one trader to another until they are in a large container shipped overseas. Then they come here to the US. Then they go into the distribution chain. Some will be sold whole, some processed into powder, and some will be blended. Then they get packed and shipped all over, to stores, to online websites. It can easily take anywhere from 3 or 4 months to close to a year between the harvest to the shelf.

Do certain spices taste differently depending on where they are from?

Definitely. For instance, Indian coriander has a very distinct floral citrus note, versus the coriander most people buy, which is Moroccan coriander, which is kind of egg shaped, and a bit yellowy. Moroccan coriander is a bit sweeter and a bit warmer, sometimes with a touch of bitterness. I use both. It’s not a matter of better or worse, it’s just different. There are also two main types of cinnamon: The harder bark found in most US markets, which is called cassia, or sometimes referred to as Chinese cinnamon. Cassia is very rich in natural oil, so it has a very distinct cinnamon scent.

Then there’s the softer bark from Sri Lanka, referred to as Sri Lankan or soft-stick cinnamon, or what the Mexicans call canela, which is more floral and delicate and harder to get. It’s made of very thin, rolled layers. You can break it very easily with your hand. It’s not as harsh as the cassia can be. Then you have cinnamon from Vietnam that is even richer in natural oils, and the bark is much thicker, so you mainly find it ground because there’s no way you can use it at home. All types are called cinnamon in the US, but in certain countries there are laws that only true cinnamon from Sri Lanka can be called that.

How do you come up with the blends?

There’s a story behind each blend. One of my philosophies in life is that if you do something and there’s no story behind it, there’s no point. We can all speak, but that doesn’t mean we have something to say. I am inspired by people, places, dishes that I ate. Then I start to think about how to translate that experience into a seasoning. For me, making a blend is like inviting people over for a party. Some people work together and it’s a success. Some people do not and it’s a compete disaster. With spices it’s the same thing.

First I draw a list of the spices, then measure them, because everything is scaled to the gram—I’m not just throwing things in the air. Then there’s the visual judgment, as far as colors and quantities. Then there’s the toasting, deciding which of the spices are going to get toasted and for how long, then which grinder am I going to use, if I want to achieve either a fine powder or a coarse texture. Some spices will be left whole if that serves a purpose. Then there is the smelling, which is key, then the flavor, the taste. The fact that I cooked and baked for 19 years allows me to explore a variety of cooking options before I even decide to feature the blend to the rest of the world. I boil them, grill them, fry them, play around with them to see what will work best. Then I also leave them alone for a while, just to see how they develop over the course of weeks or even months—to really get a full picture of not only what they are now, but also what they’re going to be 10 months from now.

How do you decide which spices should be finely ground, which ones left coarser?

It’s again a question of what they’re going to bring to the blend. Sometimes I might grind the coriander seeds completely into powder because I’m not looking for a textural aspect. As a powder you will taste the coriander right away, as soon as it dissolves in your mouth. Whereas if I left the coriander whole or just cracked, you will have to start chewing on it, so you’ll get the coriander note later on. So do you want to taste the coriander now or later?

Source: http://www.foodandwine.com/articles/lessons-from-lior-lev-sercarz